As the end of the exam season arrives, unsurprisingly, government ministers are pushing forward to comment on the state of education and teaching. It is a pattern that, in the UK at least, seems to be repeated year on year.

In today’s Telegraph, Liz Truss announced that:

Teachers must stop “reinventing the wheel” by drawing up special lesson plans for children and revert to traditional teaching from text books – The Telegraph 26/6/14

Fair enough, so it seems based on the article – teachers spending too much time planning lessons and printing worksheets rather than teaching – it would be difficult to disagree…that is, if this was indeed the case.

However, Miss Truss goes on to refer to “strong core material” and that is at the heart of the problem – it doesn’t always exist. In my main teaching subject, English, the quality of text books for GCSE is rather poor. Lots of bright colours, text boxes, pictures, but very little decent content. These books are fine for a lesson or two, but any child whose entire English course was taught from the current crop of text books (or for that matter, some of those from the ‘halcyon days’ of O Level) would be short-changed indeed.

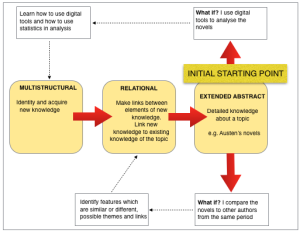

Many English text books follow a very similar format – a short text extract, several mundane questions based on the text and then an imaginative writing task – over and over again, without any real development in knowledge or challenge. As text books aim to cover all possibilities, and knowing that schools have increasingly limited budgets, they often cover most of the literature set texts in a page or two of surface level information.

The attitude Miss Truss reveals is one that suggests that if only teachers stopped faffing around and taught from ‘the text book’, all would be right with the world – it also suggests that this is all there is to teaching. This certainly seems to be the party line, that anyone, qualified or not, can roll up and teach a class. A job made laughingly easy when all you have to do is tell the class to ‘open your text book at page 23 and answer questions 1 to infinity’ while settling down with a coffee for a little gentle marking. Sadly, teaching is not that easy and the miracle ‘core’ text book is currently a fantasy.

In reality, things are not so straightforward. Good teaching means using the available resources and adapting them for the pupils in a particular class, which can take time. Yes, spending hours creating clip-art laden worksheets which achieve little is pointless, but so is getting pupils to work mindlessly from a text book without considering whether it actually meets their educational needs. I suspect that much of the time spent on ‘lesson planning’ is actually for the benefit of OFSTED or, more likely, OFSTED-obsessed SMT. The focus on differentiation and individually tailored lessons, criticised by Miss Truss, is a direct result of Government pressure for all schools to be ‘good’ or better. This in itself is based on Michael Gove’s flawed logic:

Q98 Chair: One is: if “good” requires pupil performance to exceed the national average, and if all schools must be good, how is this mathematically possible?

Michael Gove: By getting better all the time.

Q99 Chair: So it is possible, is it?

Michael Gove: It is possible to get better all the time.

Q100 Chair: Were you better at literacy than numeracy, Secretary of State?

There is another problem, for decent text books to exist there needs to be several years of stability within the examination system. A text book is likely to take a year or so to create and publish – difficult to do well when as soon as it is published it is obsolete (remember all those text book chapters on controlled assessments?). In addition, there are currently multiple exam boards in England and therefore, unless there was a single board and a single syllabus, there would never be a single, definitive text book. Currently, the major publishers each tend to focus on a single exam board, knowing that schools teaching that board would be likely to buy their book. If we had a single board for each subject then some healthy competition might develop between publishers to produce the best text book – at the moment this is simply not the case.

A similar problem exists for English departments (and every other school department, I’m sure) – every time the syllabus changes or the set texts change, hundreds and thousands of pounds have to be spent on buying new stock, money which is increasingly hard to find. If I wished to teach, for example, Jane Austen’s ‘Emma’ (assuming it was on the syllabus) I would need copies of the text to use in class (for those who can’t or won’t buy their own copy) and perhaps additional clean copies for the final exam. This all costs money. There is no text book for ‘Emma’, so it would be necessary to create suitable tasks (something that I would do anyway, even if there was a text book as it is unlikely that one book could cover everything my class would need). Or should I be limited to teach only those texts with an existing text book? Hardly the challenge and rigour so favoured by the Government.

Now, I try not to be too cynical about education and politics, but is there, perhaps, a darker reason for this panegyric on text books? It may be interesting to note that the education secretary, Michael Gove who advocates a return to ‘traditional’ teaching, used to write a column for The Times (a NewsCorp company) and received an advance from Harper-Collins (a NewsCorp company) for a book which he has not yet written (listed on the Register of Member’s Interests)…and that Harper-Collins is a major publisher of educational text books. But, surely that is all just coincidental?